3015-humboldt-county-california

HumboldtCountyRedwoodTreesNearFerndaleCA

yurok-map

yuroklogo

Place Category: Specialized Court Projects

- YUROK TRIBE – CRIMINAL ASSISTANCE PROGRAM – MEMORANDA OF UNDERSTANDING WITH DEL NORTE AND HUMBOLDT COUNTIES

- PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

- PLANNING & IMPLEMENTATION

- PROGRAM OUTCOMES

Summary: In 2009, the Yurok Tribe entered into agreements with Del Norte and Humboldt Counties to exercise concurrent jurisdiction over non-violent cases involving Yurok offenders.The agreements authorize the state and tribal courts to share responsibility for supervising eligible offendersand establish protocols for transferring cases to the tribal court’s Wellness Court for treatment, culturally-relevant services, and compliance monitoring.

Tribe:

Yurok Tribe

Program:

Memoranda of Understanding with Del Norte and Humboldt Counties

Program Running Length:

2012 – Present

Contact:

Jessica Carter

Phone: (707) 482-1350 ext. 1335

Fax: (707) 482-0105

[email protected]Yurok Wellness Court

230 Klamath Blvd.

P.O. Box 1027

Klamath, CA 95548

www.yuroktribalcourt.orgLocation:

Klamath, California

Land Characteristics:

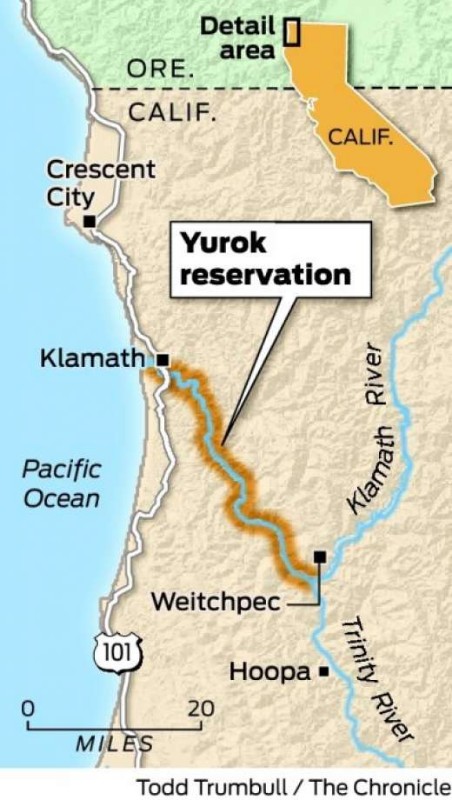

The Yurok Reservation is located on 63,035 acres along a 44-mile stretch of the Klamath River in Northern California. The reservation stretches over parts of two counties, Del Norte and Humboldt. It is bordered by the Hoopa Indian Reservation to the south and Redwood National Park to the west.

Population:

The Yurok Tribe is the largest tribe in California, with over 6,000 enrolled members. The Yurok Reservation has roughly 1,000 residents, mainly concentrated in the town of Klamath.

The State of California has criminal jurisdiction over the Yurok Reservation pursuant to Public Law 280. As a result, Yurok tribal members who commit crimes, whether on the reservation or off, are charged by state prosecutors, and their cases are heard in state courts. Likewise, tribal youth who commit acts of delinquency enter the state juvenile justice system. State authorities are not required to notify the Yurok Tribe when a tribal member is arrested.As a result of these jurisdictional complexities, there are a significant number of Yurok tribal members involved in the state court system, where they do not have access to culturally-relevant services and where the Yurok Tribe has no ability to determine how these cases are handled. Recently, however, Yurok leaders decided to change this situation by approaching the state court system about the idea of transferring cases involving tribal members to the Yurok tribal court.The Yurok Tribe’s agreements with Humboldt and Del Norte counties apply to adult tribal members with criminal cases and juvenile tribal members with delinquency cases in the state court system.The Yurok Tribe’s jurisdiction-sharing agreement with Del Norte and Humboldt Counties is the culmination of a process that started several years ago. In 2009, the Yurok Tribe created its Wellness Court, which addresses substance abuse among community members by combining traditional principles of restoration and healing with evidence-based practices from drug courts. Like other Wellness Courts (or Healing to Wellness Courts) around the country, the Yurok program uses a non-adversarial team approach to link participants with substance abuse treatment, supportive services, and court monitoring to promote recovery and community reintegration. The program seeks to improve the long-term health of individuals and families and reduce crime.

By expanding the tribe’s capacity to supervise offenders and provide court-monitored treatment services, the Wellness Court opened the door for the Yurok Tribe to get involved in state criminal and juvenile delinquency cases involving tribal members. The tribe approached officials from Del Norte and Humboldt Counties and proposed taking on responsibility for supervising tribal members sentenced to probation in nonviolent criminal or juvenile delinquency cases. County officials agreed that this kind of arrangement would benefit not only the tribal members being supervised, but also the county and tribal justice systems. The counties would have fewer offenders to supervise, and the tribe could—for the first time—have the ability to offer tribal offenders culturally relevant services and supports in the community.

With a verbal agreement in place, tribal court officials began drafting Memoranda of Understanding for the county and tribal authorities to sign. In August 2012, the MOUs were executed, and the county courts immediately began transferring cases to the tribal court for supervision and services.The Yurok Tribe’s goal in developing the MOUs with Del Norte and Humboldt County was to play an active role in supporting tribal members when they have cases in state courts. After decades of watching tribal members go through state courts, the tribe wanted the ability to intervene in these cases and determine, to the extent possible, how to handle criminal and juvenile delinquency cases involving tribal members.

The MOUs have allowed the tribe to assume responsibility for supervising tribal members on probation while helping them get the treatment they need to live a crime- and drug-free lifestyle. In addition, the MOUs have made it possible for the tribe to reintegrate tribal members into the culture and life of the Yurok community.

The MOUs developed with Del Norte and Humboldt Counties establish protocols for transferring cases to the tribal court, enable the tribal court to monitor tribal offenders on probation, and provide for state court recognition of tribal court orders.

The Yurok Tribe’s MOU with Humboldt County provides for the joint supervision of tribal members sentenced to ankle monitoring for curfew compliance and alcohol consumption. This process begins when the tribal court recommends that a tribal member be referred by the county court for joint supervision. If the county court agrees, it grants joint supervision and refers the offender to the tribal court, which is then responsible for monitoring the offender’s compliance with the terms of probation, delivering services, and reporting any violations to the county court. The tribal court establishes a case plan and a weekly schedule to help each participant meet the terms and conditions of their probation. Case plans typically include drug testing, treatment, and cultural activities.There are two MOUs with Del Norte County which provides for the concurrent jurisdiction and supervision of adult and juvenile cases. The MOU pertaining to the concurrent jurisdiction of juvenile cases, enables the County and Tribal court to coordinate the disposition of juvenile cases. Working together, the two courts make a joint determination about which jurisdiction will handle the primary disposition of the case, but the case supervision and provision of services is handled by the Tribal court. Once the youth signs an accountability agreement, the Tribal court develops a case plan and provides culturally appropriate services and activities that aid in the rehabilitation of the youth. The state court case is postponed while the youth is being supervised by the tribal court.

The second MOU with Del Norte County coordinates dispositions involving adult Yurok offenders. The Del Norte MOU establishes protocols that allow the state court to acknowledge concurrent jurisdiction and the possibility of the Tribal court petitioning for the transfer of cases from the county and/or direct citation into tribal court, bypassing the county court system entirely.

The MOU also establishes an agreement between the Tribal court and the Del Norte County Probation department. The Del Norte County Probation department agrees to screen for Native American adult offenders and to notify the Tribal Court in the event an offender, who is enrolled with the Yurok Tribe, is cited or picked up by the Probation Department or Del Norte County/California state law enforcement. In addition, the District Attorney’s Office agrees to screen for Native American adult offenders who might be diverted so not referred via charging to the Probation Department or Superior Court. The Tribal Court agrees to establish with the District Attorney’s Office a confidential screening process using the offices of the Tribe’s enrollment for all new offenders, and to work with the Probation Department to review current files, including probationers for possible referral.

Building on the success of these MOUs with Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, the Yurok Tribe is developing several new MOUs for the transfer and concurrent supervision of additional types of cases.The Yurok Wellness Court team, which supervises juveniles referred by the county courts, is comprised of the Chief Judge, court administrator, prosecutor, case manager probation officer, social workers, and other partner agencies. At the judge’s discretion, tribal elders or cultural representatives are appointed on a case-by-case basis. The Wellness Court uses a multidisciplinary team approach to support participant. The court provides regular judicial interaction, random drug testing, substance abuse treatment, supportive services, and cultural interventions.

The Tribal court administrator is the primary staff person responsible for overseeing referrals from the County courts. The increased caseload resulting from the referrals made under the MOUs has required the Tribal court to enhance their staffing needs. The Tribal court created a new case manager position to serve as the primary liaison between the Tribal court and the County courts, while also providing intensive case management services to juveniles. A probation officer was hired to help handle the increased caseload.The Yurok tribal court learns about tribal members’ involvement in the county court system in several ways. Often, a county court official will call the tribal court to inform them of a tribal member’s case and/or arrest. In addition, the tribal court routinely monitors county court calendars for cases/arrests involving tribal members. In some instances, tribal members themselves may alert the tribal court about a pending case. This multi-layered approach has been effective at identifying tribal members’ cases.

Once a case is identified, the tribal court may petition the county court to transfer the case to the tribal court for supervision and services. If the county court agrees, it transfers the case to the tribal court but retains ultimate jurisdiction for the purposes of final disposition of the case. Following the transfer, the defendant enters the tribal Wellness Court, which is designed to help tribal members address their underlying substance abuse issues and achieve healing. The Wellness Court is typically a one-year program, but it can be extended or shortened based on individual need.

Once the case has been transferred to the Tribal court, the case manager and probation officer meet with the offender, which may either be in the Tribal court itself or while the offender is in jail. If the offender is in jail, a risk assessment is conducted, the results of which include recommendations for treatment, a determination if there is funding for Indian Health Services treatment or program. In addition to the needs assessment, the case manager and probation officer determine if there are child support obligations, housing issues and other needs. Then, if appropriate, the offender is referred to Wellness Court to develop a personalized case plan.

If the client is on probation or parole through the State of California, the case manager assists them with meeting the terms and conditions of their probation/parole, which includes meeting with their probation/parole officer and ensuring they receive substance abuse treatment.

In creating the personalized case plan, the Wellness court first looks at what the defendant’s needs and wants are, then looks at where they are in their personal life. Then a determination is made about what services are necessary for healing: in-patient treatment or outpatient services, sober living, recovery/support groups, and AA/NA meetings. The court then works with the defendant to sort out their family affairs, including setting up visits with them. The Wellness Court staff then talk with the defendant about their basic personal responsibilities as well as their cultural responsibilities. These include participating in Yurok language classes, regalia making, traditional foods, attending dances and canoe carving. It is not uncommon for the Court to order the defendant to fish for and visit with the community elders.

This cultural component of restorative justice and giving back is the most vital to ensuring that the MOUs and the Wellness Court program are a success. For the Yurok, community service is a cultural prerequisite. Requiring participants to learn traditional practices is a way to re-involve the defendants in the community and to help them find cultural grounding. For instance, if you decide you want to learn to can fish, there are three classes. First, you learn how to do it; in the second class you help out, and in the third class you help out again and then you get a supply of jars and a steamer and do it yourself. If you want to learn how to smoke fish/meat, it’s the same process. The third time community members go to your house and build a smokehouse for you.

The defendant appears monthly in front of the tribal court for updates on their progress and treatment. The defendant also appears before the state court every six months where such appearances are subject to graduated monitoring. There is very little interaction between the defendant and the state probation. Instead, Tribal court officials appear with the tribal member in state court but the proceedings function more like a probation report. In reporting back to the state court, the Tribal probation officer informs the state probation officer of any issue that arises and both parties collaborate on ways to figure the out the situation. As for regular reporting, since Tribal court staff and state court staff are in the same court often, there is constant communication between both sides which results in no surprises in either court.Although the MOUs themselves did not cost the Tribe or State courts anything, the capacity developed through the Wellness Program is primarily responsible for the expansion of jurisdiction and the resulting caseload of non-violent offenders and juveniles on probation.

The Tribe was awarded $1.7 million in Department of Justice funding through the Coordinated Tribal Assistance Solicitation (CTAS) across five program areas in 2009 . The application process was highly competitive and comprehensive. It required a high degree of collaboration between several tribal departments, including the Yurok Planning and Community Development Department, the Yurok Tribal Court, the Yurok Department of Public Safety, the Yurok Social Services Department. The Tribe was very successful, receiving ae high number of program awards.

The grants were used to bolster existing tribal services as well as to create new ones to address issues across the Tribe, including the development of the Yurok Wellness Court. This funding will help to strengthen the Yurok Wellness Court in ensuring cultural alternative program services for non-violent offenders in Humboldt and Del Norte counties.

In 2011, the non-profit organization established by the Tribe, Hoh-Kue-Moh, was awarded the criminal Legal Assistance Program grant which was used to enhance the Tribal Court by providing effective legal assistance to safeguard defendant rights; increase indigent Yurok members’ access to the tribal justice system by providing legal assistance, advocacy, and mentorship for self-represented litigants; and establish culturally-relevant community service restitution or restorative justice options for indigent tribal members. With the grant, the tribal non-profit sought to enhance the Yurok justice system by implementing a self-help legal services center and alternative dispute resolution program by hiring a full-time advocate and staff attorney; formalizing dispute resolution policies and procedure to address the needs of the tribe and increase the number of cases handled by the Tribal court.

In addition to these goals, the purpose of the grant was to assist defendants in navigating through state and federal criminal justice systems, divert eligible cases from state and federal justice systems to the Tribal justice system, and provide those defendants with rehabilitation, assistance and training programs.

The Tribe was also awarded a $491,482 CTAS grant in 2012 to help foster its collaboration coalition of professionals, including the tribal council, the United Indian Health Services, the Department of Public Safety and the Social Services Department. The grant was also used to serve 60 Wellness Court participants in various stages of treatment and recovery. One of the goals for this funding was to serve 60 Wellness Court participants in various stages of treatment and recoveryThe Tribal Court received initial technical assistance from the Tribal Law and Policy Institute. Court staff also attended the National Association of Drug Court Professionals conference.The MOUs are founded on the partnerships with Del Norte and Humboldt counties. The Tribal prosecutor, judge and court administrator work with the local county officials of Humboldt and Del Norte counties to exercise concurrent jurisdiction whenever possible and defer Yurok tribal members into the Wellness Court.

Additionally, within the Tribal system, there are many different departments that need to work together to provide holistic services to the participants. Within the Wellness Court alone, the justice advisory board consists of members of the court, prosecutor, social services, police, education, Community development, tribal council, and community members. Also, there are five contracts with various treatment facilities to readily provide residential, outpatient and transitional living for Wellness clients, including state and county run, tribal specific and the Friendship House in San Francisco.Chief Judge Abby Abinanti approached the state court judges in the neighboring Del Norte and Humboldt Counties, with whom she has had a long professional relationship. Those relationships made it easier for the state court judge and other officials to trust the idea brought by the Yurok Tribal Court’s Chief Judge.

The main factor contributing to the success of the MOUs is the fact that parts of the Yurok reservation is located within Del Norte and Humboldt counties. This has enabled a close personal and professional relationship to develop between Tribal court officials and those of the County courts. The respect and appreciation earned over decades has allowed the two entities to work together to make their communities better. Judge Abinanti’s personal relationships with State and County justice practitioners and officials was a contributing factor in developing credibility within the partner jurisdictions. State judicial officers previously worked with Judge Abinanti when she served as a California Superior Court Commissioner for the City and County of San Francisco. This relationship allowed the country justice officials to feel secure allowing offenders to be monitored and provided treatment and services by the Tribal court because they believed justice would be served.

Additionally, the breadth of services provided by the Wellness Court, as well as its successful treatment of participants has provided the County courts with the needed confidence to continually engage in concurrent supervision of cases. The Wellness program services are anchored in the authority and encouragement of the Yurok Tribal Judge who holds the participants personally accountable in a culturally responsive and respectful manner. The Tribal court does not take its responsibility over the tribal members lightly which shows in the way the offenders are assisted in navigating negative experiences in a positive and healthy way through the Wellness program. Instead of acting like a facet of the judicial system, the Wellness Court team acts as the senior members of the extended family, ushering each participant back into harmony.California is a PL 280 state, which disqualifies the Tribe from receiving funding for tribal court development from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). However, the Yurok tribe has received grants to fund its tribal court programs, such as the Department of Justice CTAS grants.

Another challenge is building relationships while potentially facing a lack of confidence from the potential partners. In this case, the county officials lacked confidence in the Tribal court because they were unaware of the competence of the Tribal court, which made them nervous and less receptive to the idea of partnering with the Tribal court. Judge Abinanti dedicated years of effort to building trust with the county officials and establishing credibility of the Tribal court. The Tribal court was able to demonstrate their capacity for dealing with tribal members within their own tribal court, and provide them with services that the county is unable to provide. By constantly showing the state courts the successes, it makes the relationship less stressed and there is more trust for the Tribal court, which leads to more cases transferred to the Tribal court.

For jurisdictions seeking to replicate the MOUs, an intensive effort is required to secure agreements with the surrounding state and county jurisdictions, and have the services available so the state court can see that the Tribe is able to do a good job.Funding for the development of the Tribal courts was the top priority during the growing states but now that co-monitoring and case transfer is in place, there is a lack of funding for resources, such as medication, telecommunications, electricity and personnel in each of the small communities.

Essentially this type of collaborative program requires hard work as it is very task intensive. The most important thing is the willingness to hold the line with your own people, which boils down to upholding a circle of responsibility.As of mid-2014, there have been 56 clients since 2009. 49 of the 56 are ongoing cases, with 7 new clients. There have been 24 misdemeanors and 2 felonies.

In utilizing the agreements with the counties, the Wellness Court has helped upwards of 50 tribal members achieve and maintain sobriety.Since its inception, the YWC has admitted over 160 participants. The YWC demographic breakdown reveals that a majority of YWC participation admitted to the program are between the ages of 26 and 35. This age group makes up 47% of the total participants who have been admitted to the program. Gender breakdowns are almost proportionately split with 46% female and 54% male participants. Ethnicity breakdowns are 95% Yurok, while only 5% were family members of a Yurok (either a parent and/or spouse living in the same household).

The YWC has screened a total of 234 tribal member participants for services, of which 160 were fully admitted to the YWC program. Participants entering the YWC program listed methamphetamine as their primary drug of choice (43%) followed by alcohol (29%). Both substances are highly addictive and have been particularly destructive within Yurok communities. In the last few years, we are seeing many in the tribal community turning more increasingly to illegal heroin and fentanyl use. In 2015, the Tribe’s funding for adult Wellness Court ended and participation in the adult wellness court has dropped off without these critical resources. Of those that entered the YWC a total of 60 clients have graduated and completed all program requirements. The number one reason why individuals did not complete was due to “lack of engagement” at 63 percent, this is partially due to have had only one staff available to assist clients.Once success is seen, working with the state court system gets easier. The state court system trusts the competency of the Tribal court because it can prove to the state court and to the participants that the Tribe does not grant free rides.

The Yurok Tribal Court is working with Humboldt and Del Norte County in developing a joint jurisdiction court for dependency cases.There has been strong community support for the Yurok Wellness Court. Every tribal member is affected by trauma which has resulted in the use of drugs and/or alcohol and even more so with the opioid epidemic that is affecting the community. Many tribal members know that they can turn to the Court and it is a non-judgmental encouraging place for individuals.Taos Proctor, 32, is a wellness court client. Though Judge Abinanti pokes him harshly with a long finger during a court break and quips to a visitor that he has “the manners of a stump,” she is fiercely proud of him. Pulled into the meth life, he was committed to a county boys’ ranch at 16. Next came the California Youth Authority and prison. Released at 25, he bounced in and out of jail before he found himself facing a third strike. With help from the Tribal Court’s civil access attorney, he pleaded to a lesser count after spending time in Wellness Court. It marked the first time Del Norte County Superior Court Judge William H. Follett agreed to hand a felony case to wellness court as a condition of pre-sentencing release, and then probation.

Bobby Jones, a client in a family reunification case with the county court, entered the YWC with the belief that all that was needed for him to be reunited with his children was and ability to comply with the demands of the court system. However, after time in YWC, Bobby came to realize that the challenge lay not in his ability to comply with the system, but in his ability to be a good father for his children once he was reunited. As a result of becoming part of the YWC, Bobby was able to shift his focus from fighting the “system” to seeking out the resources necessary to be a good parent.

A minor was in truancy while attending high school out of his district. YWC stepped in and worked with the Dean, the child and the parents to intervene. The child was faced with the challenge of improving his performance in school and was given the autonomy to do so. At first, he had a few set-backs, but YWC worked alongside him and his parents to explore other options. It was decided that homeschooling, along with additionally probation requirements, were the best fit for the child. He was also encouraged to attend cultural ceremonies and activities. In the end, he developed healthy relationships with other Native youth and changed the direction of his life – completed the twelve (12) months of probation, saved monies for a truck, paid fines and is seeking his drivers’ license to pursue employment.

No Records Found

Sorry, no records were found. Please adjust your search criteria and try again.

Google Map Not Loaded

Sorry, unable to load Google Maps API.